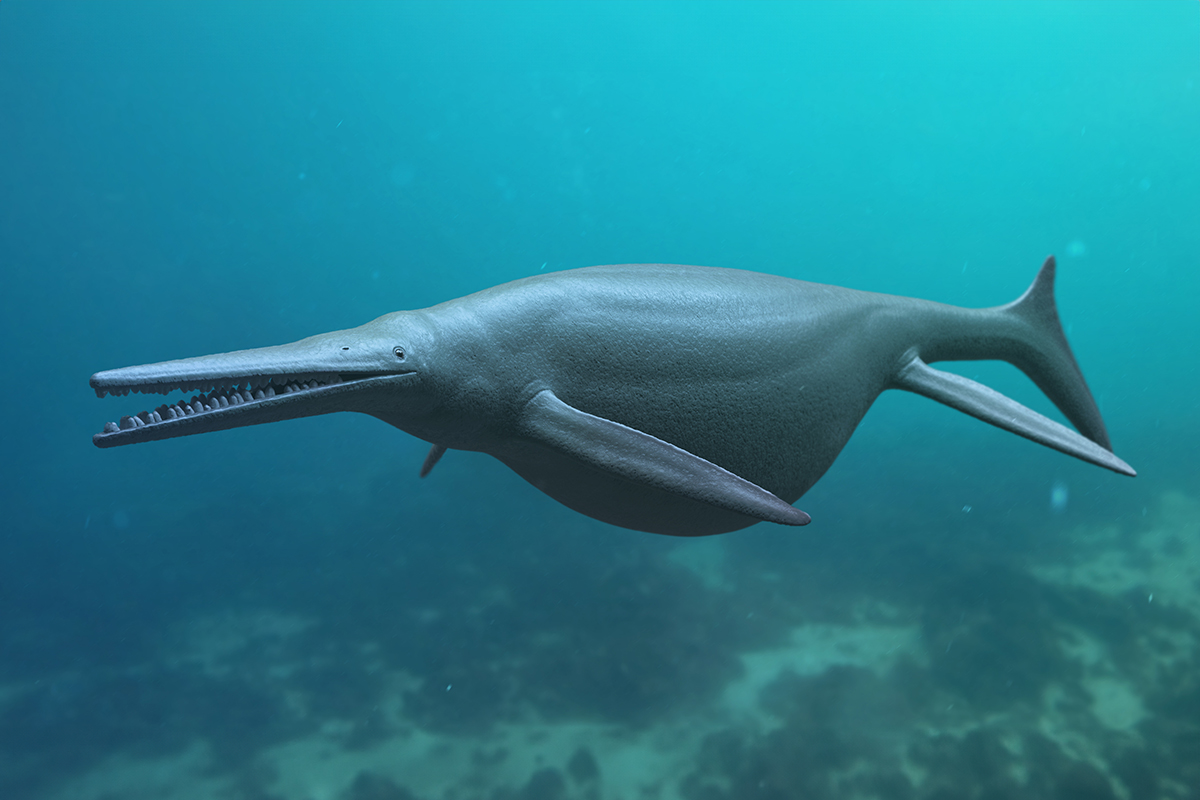

An ancient marine reptile may have consumed vast quantities of shrimplike creatures through a feeding method akin to some modern-day whales.

The reptile, Hupehsuchus nanchangensis inhabited Earth’s waters approximately 247 to 249 million years ago in the early Triassic Period.

Initially found in China in 1972, the understanding of this reptile’s eating habits and way of life remained elusive due to the poor preservation of its skulls.

Recently, two fossils were extracted from Hubei’s Jialingjiang Formation in China. These included a near-complete skeleton and significant parts of another reptile’s body.

Upon detailed examination of these fossils, scientists observed that Hupehsuchus nanchangensis possessed a toothless snout with a slender skull. Its unique jaw structure allowed it to enlarge its mouth, reminiscent of the filter-feeding process seen in modern whales.

This discovery was shared in a recent BMC Ecology and Evolution journal article.

The fossils showcased how the reptile’s elongated snout comprised unfused, thin bones. This structure is found in modern baleen whales with a flexible nib, enabling them to consume small prey in large quantities, explained Long Cheng from the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey.

Comparing the Hupehsuchus skull with 130 contemporary aquatic animal skulls revealed similarities with baleen whales. Today’s bowhead and right whales use baleen plates to sift through water and consume vast amounts of tiny sea creatures.

The fossils hinted that this reptile might have used a similar mechanism, although no definitive baleen evidence was found. Signs of structures that could support filtering were present, resembling baleen whales’ keratin strips.

Li Tian of China University of Geosciences Wuhan pointed out the similarity between the baleen structures in modern whales and the grooves and notches in Hupehsuchus’s jaws. This indicates that Hupehsuchus might have evolved its unique form of baleen.

Considering Hupehsuchus’s body structure, he likely wasn’t a swift swimmer. It probably widened its throat to consume water and filter out its prey. The reptile might have evolved these traits due to competition for food.

This development exemplifies convergent evolution, where unrelated species develop comparable traits. Zichen Fang from the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey expressed their astonishment at finding such adaptions in an ancient marine reptile.

Whales developed their filter-feeding mechanism around 17 million years post the Cretaceous Period’s conclusion 66 million years ago. In contrast, similar adaptations appeared in marine reptiles like the hupehsuchians almost 5 million years after their existence.

Michael Benton, from the University of Bristol, emphasized the remarkable speed with which these marine reptiles transformed ecosystems after a significant mass extinction event.

The findings about Hupehsuchus nanchangensis shed light on the intricate tapestry of Earth’s prehistoric marine life and emphasize nature’s remarkable resilience and adaptability. Even after mass extinctions, life finds innovative ways to thrive, adapt, and dominate ecosystems. As modern humans grapple with understanding and protecting our current marine ecosystems, such revelations remind us of the eternal dance of evolution and the mysteries still hidden within Earth’s ancient depths.